Martin Flavin, 1943

1943 Harper Prize, 1944 Pulitzer Prize

The book seemed pristine, unread. I was almost afraid to open it. But not a hundred pages in, I find a yellow stain of I know not what and a burgundy stain like the wine I’m afraid I will spill on it would make.

And there’s death again. I used to be a reader and a writer – that used to be who I was, or at least who I thought I was. But I gave that up. It’s been several years now. And it’s not like I haven’t read at all, but I’ve read few novels. Novels, I have thought, are very stressful, and once I no longer expected reading to help me grow in wisdom or in skill as a writer, I simply read what was easy and interesting – history, biography, and often magazines instead of whole books – and forgot all of it pretty much immediately. Yet my suicide as a writer was a surprisingly big commitment – it took a long time and required wrenching effort to complete – and I’m really not sure reanimation is actually painless. So do I really want to resuscitate my writer self?

The resuscitation would reflect the one truth I know. In life – or perhaps I should say, in the universe – death produces life. Everything dies to feed the next thing up on the food chain. That’s pretty simple: a cold hard fact, as they say. Dare I extend that thought metaphorically? Dare I consider if experience reflects a similar process? Pain is not quite death, and growth isn’t exactly sustenance. Does pain always bring growth? Does growth always follow pain? Does the growth make the pain worth it? Could my life as a writer be resuscitated and fed on the pain of the past? Do I want to undergo that experiment? I have, thus far, pushed that cup away from me.

Compost. Truth. Hmmm.

And, if I commit, do I write in first person or do I invent a character and write in third person, and, whichever I choose, how much of it is really me anyway? If I write in first person, I’m only distilling and chasing thoughts I’ve really had, blending them with bits and pieces of experience – it’s not an autobiography.

And if I write in third person, can I escape my own experience? Can I somehow avoid those thoughts of my own, chase them in some other direction? Some novels, you know, give one the feeling that much of their content is the author’s life. We, the readers, are obligingly attending as the writer processes his experiences, experiments with interpretation, figures out what they mean. It almost feels like a kind of servitude on the part of the reader.

Journey in the Dark struck me that way. It’s a fascinating, just-post-frontier world the author creates in this Wyattville, Iowa, fascinating because it’s a world I have not imagined before and because it’s so detailed; while I read, I’m there and not here. I am taken in and read with abiding interest the life story of Sam Braden, until he becomes elderly, and suddenly this lifelong progression of growth in his career – and in America as a kind of context even though part of it falls within the great Depression – is called into question. This character, created by this author, Martin Flavin, has moved through his life in a determined, steady, generally passionless manner, never questioning or doubting his own goals or his ability to achieve them. Yet suddenly when his son, with whom relations are strained, marries, impregnates his wife, mends things, and promptly heads for war – World War II – he realizes for the first time that his life has been, well, soulless, and that his generation has created that situation in which “all you fine young men … must suffer for our faults … and … must remake a world which we have wrecked.” Sound familiar?

He was among the winners in a race “in which, as it turned out, there were not any winners since there were not any stakes – no real reward for winning.” He wasn’t more guilty than others of his generation because only the winners had the opportunity to find this out.

As I read this novel, I felt the whole enterprise was just a little dodgy – I did feel like I was reading something about Martin Flavin that he wanted to work out rather than a story told for my amusement. And then when it turned out that we readers had been forced to suffer the same indignity as Sam Braden – to endure with him his life only to find the experience had meant nothing – I, for one, felt cheated.

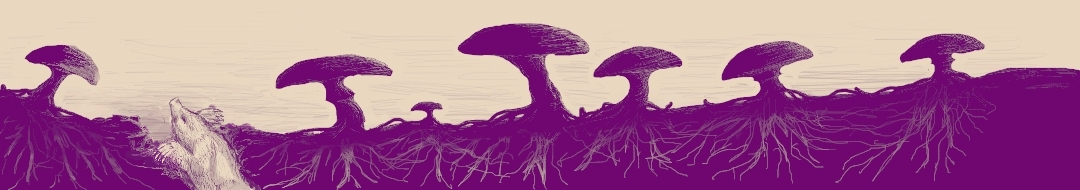

Indeed, there is this: every reading of a novel is a kind of death. The book colors every moment of your life while you read it, so that you’re always in the world of the book and never really, truly in your own, and then it’s over. The whole world of the book dies when it ends. Even the dead characters die another death because their memory in the characters left alive dies with those characters.

And there’s also what sort of end a novel makes for itself. Awfully hard, I think, to make a good end. How do you kill a whole world and kill it well?

Personally, I don’t think Martin Flavin got it, at least not in Journey in the Dark.

Stevedore – dock laborer

Calaboose – jail

What is A Bookful Bequest? Read about Hannah Grachien’s Literary Circumlocutary

Coming soon: Willa Cather’s My Antonia